Chapter 1 What is an Option?

You might have heard stories about making $100,000 in a week trading stock options, after starting out with $5,000 (or less) in the bank. What are options? How did they do that? Can I do that? You probably can, and we’ll dissect some of those winning trades later. But first, we have to go over what an option is.

1.1 Options Contracts

You’ve been eyeing this $500 treadmill for a while, but you know you won’t have the money to buy it for about 6 months. You have to wait, but you don’t want to pay more than $500. You talk to the store manager to see if they can sell you the treadmill for $500 or it’s price 6 months from now, whichever is cheaper. To your amazement, they agree but say you have to pay $25 now to lock in the deal. You don’t really want to pay $25, but you can come up with it and you really want that treadmill. So you do it.

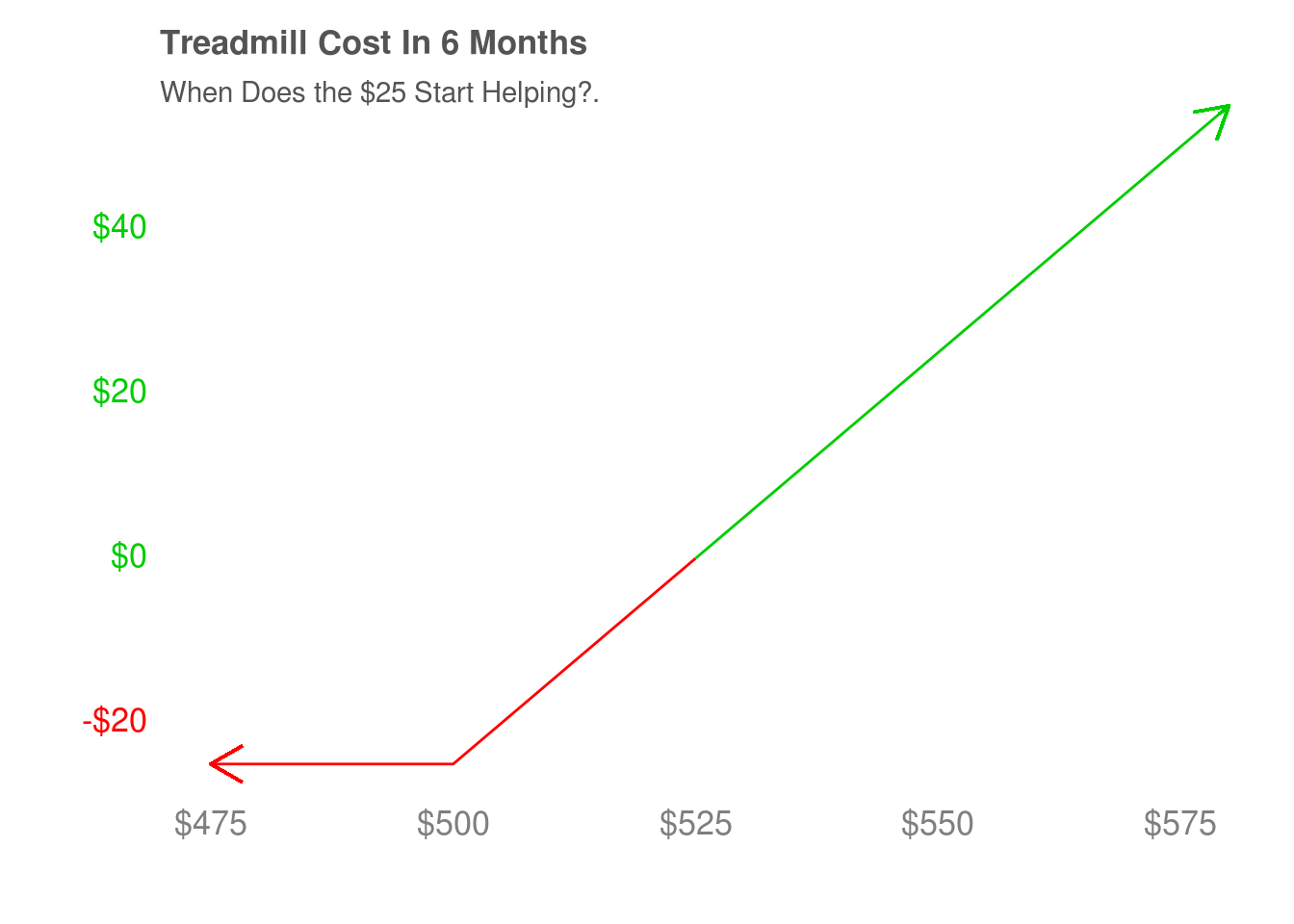

This is our first payoff diagram. They’ll get more complicated as we go along, but they’ll always be color-coded so that we can see the key information with a glance. The plot shows when the $25 fee starts saving you money. The line is green above $525 (so it saves you money), and red below $525 (so it costs you money). You save $0 if the treadmill costs $525 6 months from now, so you’ve “broken even” on the deal. So we call $525 the breakeven (price). The plot tells us you start losing money when the treadmill costs $525, and keep losing more until it costs $500. By then, you’ve lost $25 and can’t lose any more.

Let’s break down the information in the diagram. Remember that you actually agreed to buy the treadmill for $25 up front, plus the smaller of $500 and its price 6 months from now. If the treadmill is less than $500, you spent that $25 for nothing because you can just buy the treadmill for less than $500. If the treadmill is between $500 and $525, you save the difference between them. That’s less than $25, so you still lose money. When it is more than $525, you can buy it for $500. So you get back your $25, plus however much more than $525 the treadmll costs. I had to use a lot of words to capture the information in the payoff diagram, so hopefully this example helps you see how helpful they can be.

Before moving on, let’s ask ourselves – why did the store ask for $25? Remember that they agreed to sell the treadmill for the smaller of $500 and the price in 6 months. If it’s below $500, they don’t make anything extra. If it’s above $500, they lose money. They can only lose by agreeing to the deal, so they won’t do it unless their paid up front. But why $25? They could have picked the number out of thin air, but it’s more likely that they used their knowledge of the treadmill market to come up with it. So how much they charge depends on how much they think the price might go up in the future. Nobody knows what’s going to happen in the future, so it’s a guess. But it’s their best guess and one they were willing to do business at. You, on the other hand, are only willing to pay so much to lock in the price at $500. So they can’t go too high or you won’t take the deal.

1.2 Options are Insurance

You bought an option from the treadmill store, a call option. A call lets you buy an item for no more than a particular price at some future date. Just like this example, the call is worthless if the item is less than that price. There’s another type of option, a put. Just for completeness, I’ve written out a more careful definition of a call and a put below.

- A call gives its owner the option to buy shares at a pre-specified price on a pre-specified date in the future. The call gives its owner protection against the price of shares going up between now and the future.

- A put gives its owner the option to sell shares at a pre-specified price on a pre-specified date in the future. The put gives its owner protection against the price of the shares going down between now and the future.

To me, options are insurance. A call protects me from the price of the treadmill going up, and a put would protect me from the price of the treadmill going down. I wouldn’t have any interest in paying for a put, because I don’t sell treadmills. But a store that has to carry a large inventory of them might want protection from the price of their inventory going down. Perhaps because they are like insurance, the price of an option (a call or put) is called its premium. There are options strategies that explicitly use options as insurance. We’ll meet one such strategy, the protective put, soon enough. But there are many other strategies that are more speculative and try to profit from the changes in the price of the option. We’ll see some of those strategies soon, too.

1.3 Pricing Insurance Contracts

What could make your car insurance more expensive? I don’t own a car so maybe my list is missing some things, but here’s what I came up with:

- How many accidents you have been in.

- Your demographics (gender and age).

- How many companies are offering car insurance in your area.

- Your deductible.

A deductible is how much you have to pay out-of-pocket before your insurance coverage kicks in. For example, if you have car insurance with a $1000 deductible, the insurance won’t cover the first $1000 it costs to repair or replace your car. The higher your deductible, the lower your insurance premium will be. That’s because you’ll end up paying more of the insurance bill, and the insurance company will pay less of it.

What could make your health insurance more expensive? Here’s what I came up with:

- If it is a “guaranteed” plan that doesn’t require a medical background.

- If it has higher maximum coverage amounts (for prescription drugs, dental, etc.)

- Your demographics (gender and age).

- If you are a smoker.

- Your deductible.

You get the idea - anything that makes paying out a claim more likely takes up the price of insurance. We can apply the same logic to calls and puts. The more likely the price movement we’re insuring against is to happen, the more expensive the option will be. A call protects you against the price going up. Say you wait 3 months to take the treadmill store up on its offer, and the price goes from $500 to $550 by then. The treadmill is already $50 more than $500, so they will charge you at least $50 to lock the price in at $500. That’s 2x (or more) what you could have bought the call for earlier. A put protects against the price going down. If the store wants to sell the treadmill for no less than $500 in 6 months, they’ll have to pay $25 for it. If they wait 3 months and the price drops to $450, that’s $50 less than the $500 they want to sell the treadmill for. They’ll have to pay at least $50 for the put, which is 2x (or more) what they could have bought it for earlier.

There’s more to pricing options, but we’ve built good intuition from this example. Here’s one last question for you to think about while we move on to a deeper dive into payoff diagrams. In the treadmill example, when the treadmill is at $500 the call you buy and the put the store buys are both worth $25. Is that realistic, or do you think one form of protection cost more than the other?